What Makes The Washington Capitals Power Play So Good?

It is no secret that the Washington Capitals have a great power play. Since Adam Oates brought the 1-3-1 formation over from New Jersey prior to the lockout-shortened 2012-2013 season, the team has gained approximately 22 goals more than league average per 82 game season because of it, or roughly seven additional standings points each season. To put that into perspective, seven points would put the Vancouver Canucks, currently last in 5-on-4 goals scored, from lottery contention into a playoff spot. It would put the New York Islanders, struggling for their playoff lives, comfortably in second in the Metropolitan division. The man advantage is the reason why the Boston Bruins -- a team that has traditionally struggled up a man but is now second in 5-on-4 goals scored -- is in third in the Atlantic and not five points out of a playoff spot.

When I began this project, I had a vision of two things. I wanted to be able to use a decently-large sample of data accumulated from six teams over the course of an entire season to conduct large-scale studies on concepts like shooting from one's off-wing, one-timer effectiveness, and so on. But I also wanted to be able to get down to the nitty gritty, to use small sample descriptive micro-stats to look at exactly what teams are doing, whether it's on zone entries or in-zone, and which players have been better at which facets of the man advantage and have what tendencies.

So today, I finally address the question that everybody seems to be asking, "what is it about this Capitals power play?" Or, more accurately, I continue that exploration, one which has essentially been the heartbeat of this website's exploration, by looking at small sample numbers that I have tracked from this season, to understand some of what the team does so well.

FACEOFFS

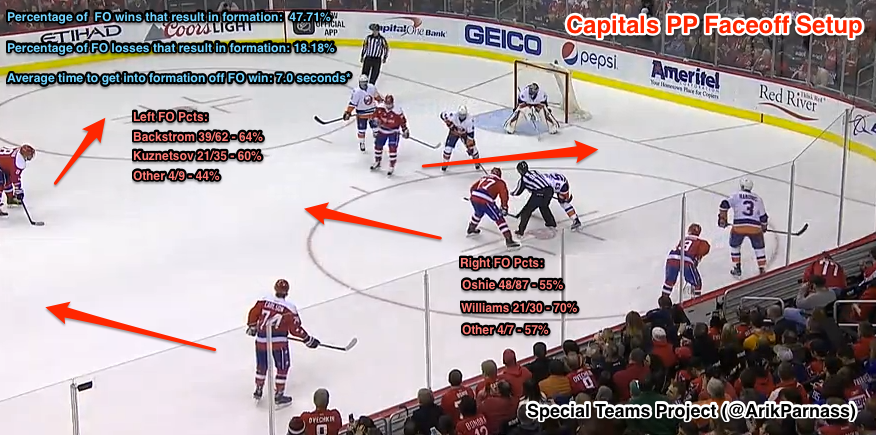

The Capitals power play has never been a league leader in faceoffs. From 2012-2013 to 2014-2015 they were 17th in winning percentage. This year they've also been a pedestrian 14th. But they do something peculiar which I wrote about while working for the team a couple of seasons ago. The Capitals always have righties take power play faceoffs on the right side, and lefties on the left, whether that be wingers or centers. The strategy has two advantages. First of all, taking a faceoff on one's strong side means an ability to swat the puck back easily on one's backhand with the ref to the inside of the stick. Second, in the Capitals' case, the right-handed right-wingers on the two power play units are also the slot players, so by starting them in the faceoff circle, it takes less time following the faceoff for the team to get into formation.

The Capitals have righties take faceoffs on the right and lefties on the left on the power play, as seen above with T.J. Oshie.

There is a lot of information in the above graphic, so take some time to peruse it. It is important to note that faceoff results can be very difficult to interpret because different buildings have different interpretations of what "winning a faceoff" means, whether that's the player to initially touch the puck or the team to ultimately gain possession. Over the first few months, I tried to stay consistent with the play-by-play sheets whenever unsure, but later changed to my own definition of the winner being the player whose team ultimately gained possession. So these results are a combination of the two, which isn't hugely helpful, but is still interesting to see.

In the top left corner, you will see the percentage of offensive zone faceoff wins and losses after which the Caps were able to gain possession and get into their proper 1-3-1 formation without the puck being cleared. The third number, average time to get into formation, is based only on the last few games -- since I adjusted my tracking method recently to be able to calculate that properly -- so take that with a grain of salt.

As you can see, the Caps like to set up with Ovechkin on his off-wing. Occasionally, as a set play, he will begin much closer to the right faceoff circle, and the center will try and draw the puck back to him for a quick snap-shot at goal. Either way, if the puck comes to Ovechkin off a right-side faceoff win, he is likely to shoot right away.

REGROUPS/ZONE ENTRIES

I've talked before about consistency and repetition when it comes to the power play, and the Capitals are a champion of that. But it doesn't only start in the offensive zone. The Capitals use a specific base zone entry, and then have a couple of additional plays they sprinkle in, while also often simply regrouping quickly in the neutral zone.

That primary play is often called a "Single Swing," and it's a fairly basic and common entry play, although the Caps are the only of the six teams I track to use it consistently. Thanks to the NHL.tv changeover and my inability to go back into old game tape for this piece, I had to borrow a GIF from Pat Holden, an analytics writer who follows the Caps closely, that illustrates what the play looks like when executed correctly. Check out some of Pat's work on Caps zone entries here.

The Capitals' Single Swing is all about reads; it really is a football play within a power play zone entry. John Carlson and Matt Niskanen, the Caps' first and second unit defensemen on the power play, first look to the swinging middle forward, usually Nicklas Backstrom or Evgeny Kuznetsov, as shown above. That forward can then pass wide to Marcus Johansson with speed on the right, or take the puck in himself. If the single swing player is covered -- the Buffalo Sabres did a great job of taking away that option earlier this season thanks to some pre-scouting -- the next read for the defenseman is directly to the right to Johansson. The third read is a long pass over to the left to Alex Ovechkin, and the fourth is either an individual rush by the defenseman or a dump-in. Ovechkin, if he is the option chosen, will either cut to the middle once in the zone to attempt a rush shot, or will ring the puck around immediately. With my poor Sports Dood skills, I attempted to diagram the play below (forgive the terrible pacing).

What I didn't mention above is that the eventual slot man, in this case Oshie, serves as a decoy, a common feature of any power play breakout, starting at the opposing blue line and skating along the line right to left to draw the closest defender away from the boards allowing Johansson, coming with speed, to enter the zone unimpeded.

The beauty of this entry for the Caps is that by having Johansson most often as the puck carrier, the puck enters the zone on the right half-wall or goal-line, exactly where the Caps want it once they're in formation; it's only one or two short passes to get the puck over to Ovechkin or Oshie for their dangerous one-timers. By creating an environment (speed, decoy, polished product) in which Johansson (or Jason Chimera, or Kuznetsov, etc.) can enter the zone on his off-wing, this entry also means the player can easily drop the puck back to the point off the boards once in the zone or rush in for an off-wing (better angle) rush chance, but also is already in the intended position for the 1-3-1. In other words, a lot of teams have players enter the zone on the strong side, and then it takes 10-15 seconds for players to get into position on their off-wings (the Tampa Bay Lightning are an example of this), but not the Caps. Every second is accounted for, and very few are wasted.

There are a number of different ways one can evaluate the success of a zone entry, and I will cover at least four of them in my zone entry studies in the next few weeks. The method I've decided to use here is that a successful zone entry is one in which the team as a result of the entry gets off at least one dangerous rush shot (shot within five seconds of the entry and below the top of the faceoff circles) or gets into formation before the puck is cleared. Because so much of Caps' PP offense comes from those two states, I felt it was most appropriate. For reference, on the left are the entry rates for each of the six teams I track using that method.

The Caps are clearly the best, with the Toronto Maple Leafs not too far behind. The New York Islanders are a team that, especially in the first half of the year, treated the power play not too differently from even strength -- not electing for a distinct formation at all times -- and as a result their numbers are likely skewed negatively by this method of evaluation. So looking at micro-stats, how does each aspect of the Capitals' entry scheme, particularly the Single Swing, contribute to that success rate?

The Capitals' single swing entry accounts for the majority of their full regroups, and it is the most, if not one of the most, successful power play entry schemes in the NHL

Above you see the Single Swing Entry diagramed, with the micro-stats for each player in each position of the breakout. There hasn't been a major difference in effectiveness between Carlson and Niskanen, and predictably Jason Chimera -- despite his blazing wheels -- has struggled a little bit as the final puck carrier on the entry, at least compared to his peers.

It's interesting that it takes the Caps 18.16 seconds to enter the zone after a full regroup, on average, but almost as much time (18.11 seconds) on a neutral zone regroup. This is because with a more improvised regroup, you are sacrificing effectiveness to save time. It is a trade-off that I will look at in its own post at a later date.

Overall, the Single Swing is more effective than seemingly improvised regroups (45 percent to 43 percent), although some of the regroups in the "other" category are following shorthanded rushes in which there are less penalty killers to weave through for a clean entry. If we remove the 17 entries that fall into that category, the difference becomes 45 percent to 41 percent, still not a huge gap, but noticeable. And if one were to apply this to other things, consider that the Caps' top-end stickhandling talent likely makes improvised entries more successful for them than they are for other teams.

Finally, stretch passes haven't been too kind to the Capitals this season. Once again because of the NHL.tv troubles, I haven't been able to look back too far into the archives -- I could have sworn there were at least a couple of stretch plays to Kuznetsov early that worked -- but there is one play in particular the team likes to use that I feel is well worth continuing to try about once per game.

A recent edition of a stretch play the Caps love to run to spring, among others, talented Russian sniper Evgeny Kuznetsov

I wish I had video of the play working, because when it does, it doesn't look like it could ever fail. I've rougly diagrammed the play below, in a form slightly different from that in the video above. In either form, the objective is to freeze defenders and then spring a streaking player up the middle for a breakaway.

If the Caps run this play successfully I will be sure to post it to Twitter. While the numbers behind whether it leads to a net benefit are so far inconclusive, I love the creativity involved. It adds a new wrinkle to an already impressive unit.

OFFENSIVE ZONE PLAY

If you're a reader of this website, you know that in the offensive zone the Capitals use a 1-3-1 formation, with specific player locations and passing options. Players know their role and what's expected of them.

Adam Oates' 1-3-1 has quietly taken over the NHL, as most teams now use some form of it in the offensive zone on the power play.

I've diagrammed with arrows the major passing lanes and plays that are possible thanks to the positioning of the players and their handedness. The formation does a great job of finding the open player, making sure said player can get off a dangerous shot, and that the shooter is a true sniper. Next to each player once again I have the names of those who most often fill those roles, along with their goals, shot attempts and shooting percentage at 5-on-4 this year. Finally, I have listed each player's 5-on-4 PSC/min. PSC stands for Player Shot Contribution, and it is a metric that Ryan Stimson constructed using data from his Passing Project. It simply combines player shot attempts with player primary passes leading to a shot attempt. So it is is a good measure of how involved a player is in driving the play and producing offense, and is less prone to variance over small samples than its goal-based equivalent: Primary Points.

(Note: I've used my own data to compute PSC/min so that I have every Capitals game up until February 3 accounted for)

It is apparent from the graphic how important Ovechkin and Backstrom are to that power play, with the gap between Carlson and Niskanen also notable. The "bumpers" or slot men -- Oshie and Williams - contribute to shots at a lower rate, but that is largely a function playing exclusively a shooting role; their shots go for a decently high percentage to make up for it.

At the bottom left, you can see how effective controlled entries and dump-ins (of which there are only a small sample) have been for the Capitals. It's interesting that more of the team's dump-ins have resulted in offensive zone possession than carry-in attempts. The speed of the Caps' forecheckers definitely helps in tracking those down, though I wouldn't be tearing down my controlled entry schemes as a result. Also, predictably, it takes longer to get into formation off of dump-ins, though as with in my faceoff diagram earlier, those samples only span a few games.

At the top right, you can see that the Caps unleash more shots when in formation, and can also see how deadly the team's stretch plays can be. Below, you can see each player's one-timer chart, as one-timers are arguably the lifeblood behind the team's power play prowess, and they give a good sense of each player's positioning and shooting involvement.

CONCLUSION

So what has this all truly told us about the Capitals' power play? The numbers back up the fact that they play the majority of the time with a clear plan of action, that the 1-3-1 has helped them to put the puck on the stick of their best shooters in dangerous areas on their off-wings, and that they have the personnel to accomplish all of these things. First George McPhee, then Brian MacLellan have done a commendable job getting players that fit the power play they want to run. Adam Oates of course deserves all the credit in the world for what he developed. And Barry Trotz deserves acclaim for not only sticking with a plan that was successful but not of his design, but also along with Todd Rierden adding their own wrinkles and features to make the group even more consistent and more dangerous. If they're smart, with a team poised to a make a run for the cup, there's a lot we still have yet to see. Can't wait.